Toward the end of my Neuroengineering degree, I was still missing 6 credits. My main focus, however, was my master’s thesis for Neuro-Cognitive Psychology, which had already been underway for four to five months by the time I realized I needed to complete one more course before the semester ended.

This put me in a difficult situation since I wasn’t registered for many courses that semester—I had been in Berlin working on my thesis the entire time. I looked into the courses I was already registered for that offered 6 credits. Only one was a good match: Clinical Applications of Computational Medicine. In this course, each group had to come up with a project that could benefit the health sector. The lecturer told me I could still participate in the final examination if I could find a group willing to accept me.

With only a few weeks left until the final presentation, finding a group turned out to be much harder than I had expected. Most groups were nearly finished with their projects and presentations. Luckily, I found a group of exchange students who still had work to do and were kind enough to welcome me into their group.

Grateful for the chance to avoid another semester just to chase 6 credits, I was ready to embrace any project they threw my way. To my surprise, they were actually working on something I found deeply fascinating: somatization.

You see, your psychological state can affect your physical health. I think every one of us has experienced this in one way or another. It was a highly interesting topic for me because I had just finished reading When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress by Gabor Maté. The book talks about different types of repressed emotions, especially stress, and how they can lead to somatic effects later on, ranging from cancer to ALS.

One particularly interesting anecdote from the book is about technicians working at an ALS center. In one chapter, Gabor Maté describes how ALS patients often share certain “characteristics.” He explains that many of them are extremely nice people who don’t know how to set boundaries. Of course, this doesn’t apply to all ALS patients, but he argues there’s a strong connection between being “extremely nice” and developing ALS.

The technicians at the ALS center, who screen patients and hand off reports to physicians, have no medical training and are not qualified to evaluate the reports themselves. However, over time, they became so attuned to the patterns in the reports that they start making remarks like this while handing the report to the physician: “The reports look bad, but I don’t think this person has ALS because they weren’t ‘that nice.’”

This anecdote highlights the profound link between how we interact with the world—and with ourselves—and our physical health. Being “too nice” often involves suppressing difficult emotions, such as stress, which people don’t want to confront.

Turning a Review Paper Around

My teammates didn’t have a technical background, so they decided to conduct a thorough review of somatization and its burden on the healthcare system. Interestingly, they hadn’t connected somatization with repressed emotions. After discussing how I could contribute to the group, they encouraged me to explore any technical angle I found relevant to the topic.

This freedom led me to pose an exciting question: Can stress be predicted from a person’s resting-state EEG data? If it were possible, I hoped to argue that such technology could be used as an early diagnostic or validation tool for somatization.

I began searching for a suitable dataset and came across the LEMON Dataset by Max Planck Leipzig. This dataset was perfect, offering neural recordings, questionnaires, and much more. Among the questionnaires, I found the Perceived Stress Questionnaire.

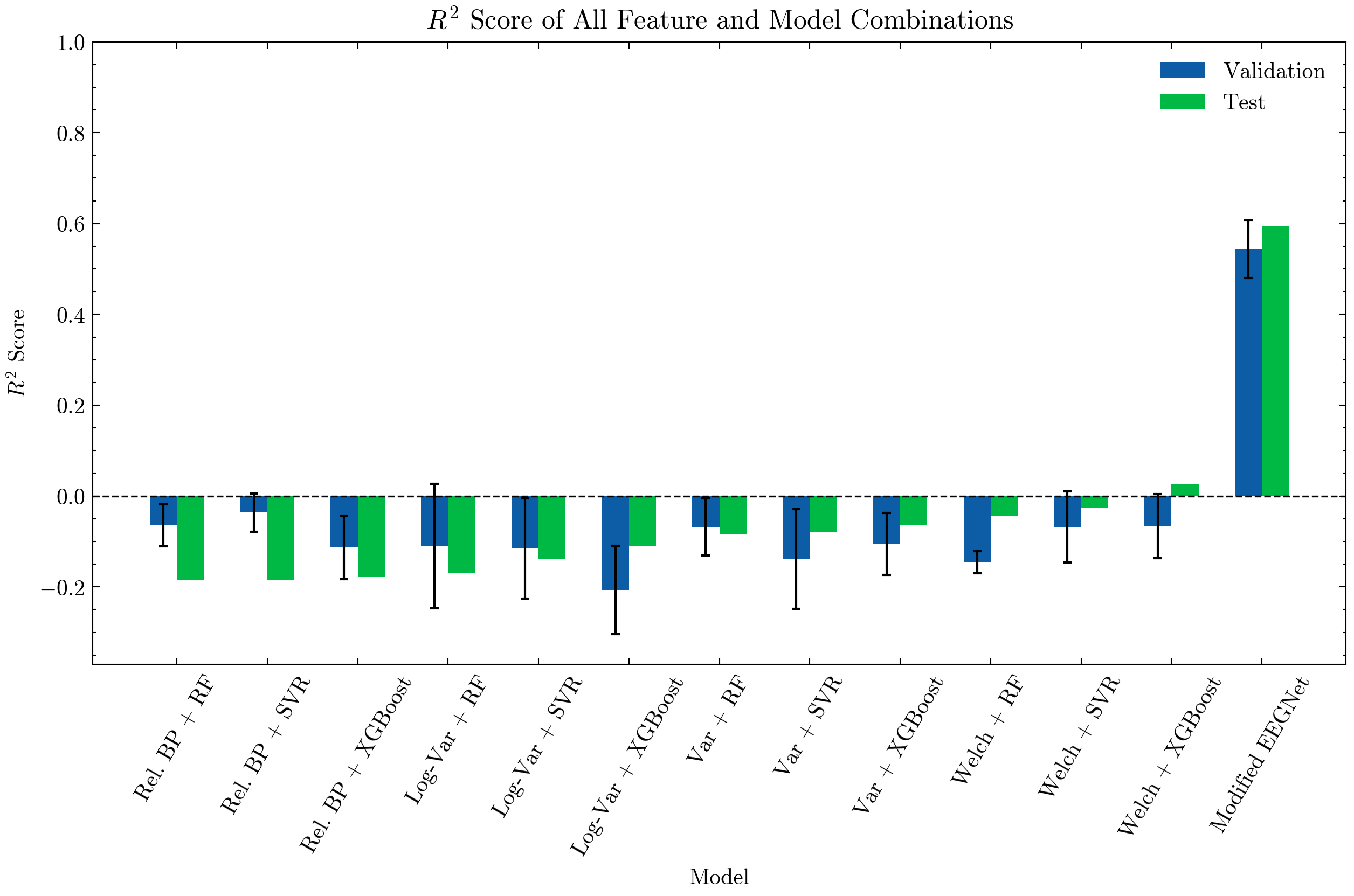

Using the resting-state EEG data, I tried to predict participants’ stress scores by extracting band power features and applying traditional classifiers like support vector machines (SVM) and random forests. Well, nothing worked…

Then, I realized I hadn’t properly learned my lesson from my previous hackathon experience: sometimes, sacrificing explainability for performance is necessary, especially when time is limited. And in this case, I only had five days to complete the project and deliver positive results for the final presentation.

So, I stepped out of my comfort zone and decided to use EEGNet as the base model for this task. However, EEGNet was designed for classification tasks, so I had to adapt it for regression. After making these adjustments, I started training the model—but again, the results were underwhelming.

After countless hours, finally, on the last day, the model started learning. It became surprisingly good at predicting stress scores. Comparing all the models side by side, I saw just how dramatic the improvement was with this deep learning approach:

Regaining Faith in EEG

While presenting these results during the final project and receiving a great grade was rewarding, my biggest satisfaction came from the realization that I had taken on an untested project. There was no prior work on this type of analysis using this dataset, and it wasn’t even clear if it would work. Not knowing the outcome, especially under time pressure, and then seeing it succeed was a huge motivator for me.

At the time of writing this post, I am actively looking for a master’s thesis that could merge into a PhD in a lab interested in exploring whether EEG signals can detect repressed emotions. My experience so far has been that many labs are hesitant to take on students with their own research questions, especially at the start of a PhD. Despite the challenges, I remain determined to pursue this project—even if it has to be a side project.

I owe a huge thanks to those last 6 credits for giving me this opportunity, to the lecturer who allowed me to participate in the course, and to my wonderful teammates who accepted me into their group when I needed it most.

Get in Touch if You Want to Learn More

As you’ve probably realized by now, I’m passionate about this project and its potential future directions. If you’re interested in learning more, don’t hesitate to reach out. Let’s figure out if you’re repressing your emotions—before it’s too late!